The U.S.

Supreme Court yesterday delivered what is likely one of the most important

copyright decisions from any court anywhere anytime. In a dramatically divided but

decisively 6-3 decision in Kirtsaeng v. John Wiley, it held that

copyright law could not be used to prevent the parallel importation into the

USA of works lawfully made outside of the USA. In other words, legally made

works can be bought and sold and resold on the “grey” (or “gray” for those not in

the Commonwealth) market, according to common sense. As the EFF says, if "you bought it,you own it"'. If you own it, you can resell it. After the “first

sale”, the copyright owner’s rights in the physical object are “exhausted” –

hence the frequent reference to the doctrine of “exhaustion”.

In other

words, copyright law will not be available to do what trade-marks law has also

failed to do, which is to serve as a tool of international trade control, price

discrimination, market segmentation and restraint of trade with respect to

legitimately made goods for which the copyright owner has been paid and in

respect of which the “first sale” has been made. Things are somewhat different in the EU - but that is not a jurisdiction that Canada would rush to emulate in this respect.

To be

absolutely clear, the copies in question were not piratical or counterfeit. The American

copyright owner got paid for these products manufactured abroad, with their

permission. However, the quest to control the resale after the first sale, to

control the channels of distribution and the pricing of the imported copies of these

products into the USA, and to generally assert a right to control sale after

“first sale” and to take advantage of higher American “what will the market bear”

pricing was denied. As the EFF says, “You bought it – you own it”. It’s not

quite that simple – but it’s now very close indeed. Basically, the owner of a

copyrighted product can do with it what he or she wishes, other than copy it or

infringe moral rights or break TPMs, where applicable.

The decision

applies to all copies lawfully made anywhere – whether the product is a book, a

chocolate bar, a wrist watch, a plane, train or automobile. It applies whether

it is the product itself that is protected by copyright (i.e. books, in this

case) or merely the packaging, labelling or other incidental aspect of the

product. It should be noted that Canada has an elaborate sui generis regime to prevent the parallel importation of books –

because book publishing has always been highly protected in Canada.

The

Kirtsaeng decision could have important ramifications for Canada. It is

consistent with the result of the six year old Supreme Court of Canada decision

in Euro-Excellence v. Kraft, which involved

copyright in a small logo on the packaging of Toblerone chocolate bars (I should

disclose that I made the prevailing argument on behalf of an intervener, the

Retail Council of Canada, in that case). The argument was highly technical, but

essentially entailed that a copyright owner cannot infringe its own copyright.

That argument carried the day in the only way that could have worked at the

time – given the very inadequate record below. The two top courts of Canada and

the USA have come to the same bottom line for most practical purposes, namely

that copyright law will be ineffective to “thwart” parallel imports of grey

goods – which are, by definition, legitimate. I’ll write a more detailed blog

comparing the Kirtsaeng case with Canada’s Kraft case in the near future.

It should be noted that some believe that the execution on paper of an assignment of copyright to a Canadian entity will entitle it to block parallel imports in accordance with the Kraft decision. However, such a tactic may very well backfire if adequately resisted. Such an assignment may be subject to attack as a sham or an abuse of copyright and may trigger unwelcome and unexpected tax consequences. More about this in the future. For now, see my comment prepared for the Law Society of Upper Canada. For practical purposes, copyright law is not a very practical way to block parallel importation into Canada.

The US decision is important to Canada for many reasons – not least of which is the imminent debate on Bill C-56, the anti-counterfeiting legislation, which includes several sometimes inconsistent references to parallel imports that could possibly have unintended or unforeseen results. Also, there can be little doubt that the lobbyists have already begun to work on Congress and the USTR to “undo” a result that some of their clients will find very difficult to accept. Such a development is a threat to Canada and other countries involved in trade negotiations with the USA, unless the negotiators stand their ground.

It should be noted that some believe that the execution on paper of an assignment of copyright to a Canadian entity will entitle it to block parallel imports in accordance with the Kraft decision. However, such a tactic may very well backfire if adequately resisted. Such an assignment may be subject to attack as a sham or an abuse of copyright and may trigger unwelcome and unexpected tax consequences. More about this in the future. For now, see my comment prepared for the Law Society of Upper Canada. For practical purposes, copyright law is not a very practical way to block parallel importation into Canada.

The US decision is important to Canada for many reasons – not least of which is the imminent debate on Bill C-56, the anti-counterfeiting legislation, which includes several sometimes inconsistent references to parallel imports that could possibly have unintended or unforeseen results. Also, there can be little doubt that the lobbyists have already begun to work on Congress and the USTR to “undo” a result that some of their clients will find very difficult to accept. Such a development is a threat to Canada and other countries involved in trade negotiations with the USA, unless the negotiators stand their ground.

Kirtsaeng

was a foreign student from Thailand studying in the USA. He figured out that he

could import perfectly legitimate text books in English printed abroad and

purchased by his friends and family in Thailand and resell them in the USA at a

lower price than other channels. The profits from his little cottage industry import

business helped finance his education. This is what most would consider to be

free trade, competition and otherwise normal, entrepreneurial, and competitive capitalism

His profits helped to finance his American university studies. The well-known

publishers John Wiley decided to stamp out this very small challenge to the

legacy business model of price discrimination based upon a tortured and

technical result that been in place if not easily enforced as the result of

lower court and two recent but inconclusive Supreme Court decisions itself over

the years.

As is so

often the case when copyright owners get excessively zealous in their quest for

absolute control, multiple and layered payments, double-dipping and other

excesses – they sometimes get more than they ask for. In this case, Wiley and

an impressive alliance of amici representing the US copyright establishment went

after a foreign grad student working his way through college. They must have

been very pleased when a jury whacked him with $600,000 in statutory damages.

But he appealed and Wiley and its supporters got a resounding defeat in the US

Supreme Court that will be seen as a huge setback in the legacy book

publishing, movie, music, entertainment, and more unenlightened quarters of the

software sectors.

However,

Wiley and other American copyright owners in various legacy and IP maximalist

sectors believe that they are entitled to segment markets, practice international

price discrimination and to charge what the market will bear in various

geographic markets. Canadians are familiar with having to pay higher prices

than Americans for precisely the same product – in part because not all

Canadian importers are as aggressive as they could be in sourcing the perfectly

legitimate “grey market” for “parallel imports” that would save their customers

money and earn themselves greater profit.

Young Mr. Kirtsaeng, however, was undeterred. He succeeded in slaying

the giant that even mighty CostCo had failed to successfully confront in the 2010

US Supreme Court in the 2010 CostCo v. Omega case.

At the risk

of seriously oversimplifying some

complex jurisprudence and its consequences, the Americans have now caught up to

Canada and perhaps even passed it for the moment with respect to “international

exhaustion”, free trade and a judicial distaste for using IP laws for purposes

for which they were never intended. Like, the Canadian decision, the US Court

today was sharply divided – although the result and the splits are much clearer

in the US case. The 6-3 arithmetic speaks for itself in this instance.

As per the Court’s summary, BREYER, J.,

delivered the opinion of the Court, in which ROBERTS, C. J., and THOMAS, ALITO,

SOTOMAYOR, and KAGAN, JJ., joined. KAGAN, J., filed a concurring opinion, in

which ALITO, J., joined. GINSBURG, J., filed a dissenting opinion, in which

KENNEDY, J., joined, and in which SCALIA, J., joined except as to Parts III and

V–B–1.

Note the additional shades of grey added by the Kagan + Alito concurrence and the partial reservation of Scalia's concurrence with Ginsburg and Kennedy.

Note the additional shades of grey added by the Kagan + Alito concurrence and the partial reservation of Scalia's concurrence with Ginsburg and Kennedy.

Court watchers will immediately note that

this alignment has nothing to do with traditional “liberal” v.

“conservative” or partisan appointment

divide. Nor can it be said to reflect any “activist” v. “strict constructionist”

divide. If anything, it may portend an emerging meeting of the minds of of a

“purposive” and “libertarian” approach to intellectual property – and the solid

rejection of the “maximalist” copyright views that one had come to expect from

Justice Ginsburg, normally considered to be a “liberal” on other issues.

The result is not surprising for any who

heard the oral argument – which featured a “parade of horribles”– including why consumers and users’ rights in

everything ranging from library books to used cars was on the line, if the

overreaching position of Wiley and its supporters had been accepted. In the

end, even the Government’s lawyer admitted that Kirtsaeng and his amici

supporters’ list of “horribles” was “worse” (i.e. presumably even more

horrible) than the alternative list.

The result is effectively a stinging rejection

by her colleagues of Ginsburg, J.’s widely noted “obiter dicta” in the Quality King

case a few years earlier. That case involved shampoo products that had

been made in the USA, shipped abroad and imported back. She provocatively opined

by way of obiter dicta in a

concurrence that:

This case involves a

“round trip” journey, travel of the copies in question from the United States

to places abroad, then back again. I join the Court’s opinion recognizing that

we do not today resolve cases in which the allegedly infringing imports were manufactured

abroad. See W. Patry, Copyright Law and Practice 166—170 (1997 Supp.)

(commenting that provisions of Title 17 do not apply extraterritorially unless

expressly so stated, hence the words “lawfully made under this title” in the

“first sale” provision, 17 U.S.C. § 109(a), must mean “lawfully made in the United States”); see generally P.

Goldstein, Copyright §16.0, pp. 16:1—16:2 (2d ed. 1998) (“Copyright protection

is territorial. The rights granted by the United States Copyright Act extend no

farther than the nation’s borders.”). (emphasis added)

This time around, Wiley relied upon a passage

from the majority in Quality King. In Breyer, J.’s words:

We cannot, however, give the Quality King statement the legal

weight for which Wiley argues. The language “lawfully made under this title”

was not at issue in Quality King;

the point before us now was not then fully argued; we did not canvas the

considerations we have here set forth; we there said nothing to suggest that

the example assumes a “first sale”; and we there hedged our statement with the

word “presumably.” Most importantly, the

statement is pure dictum. It is dictum contained in a rebuttal to a

counterargument. And it is unnecessary

dictum even in that respect. Is the Court having once written dicta

calling a tomato a vegetable bound to deny that it is a fruit forever after? (Emphasis

added)

As for her controversial

passage mentioned above, Justice Ginsburg admitted that her comment in Quality

King was “dictum” but went on to say that “I disagree with the Court’s

conclusion that this dictum was ill considered.”

Kagan, J. in

her concurrence indicated that if Congress views yesterday’s decision “as a

problem”, “it should recognize Quality King—not

our decision today—as the culprit.

The Kirtsaeng decision gets very technical, as inevitably do all decisions on parallel imports if adequately briefed and reasoned. It goes into great depth based upon the interplay of key sections of the US legislation. But, in the end, it all boiled down to the common sense interpretation of five words: “lawfully made under this title”. In the end, the Court agreed with Kirtsaeng that this phrase was not subject to geographic limitation and applied to copies lawfully made abroad.

There is already much speculation

about whether this decision could be a premonition of a surprise outcome in the

pending Bowman v. Monsanto case about whether and how the “exhaustion” doctrine

applies to patented seeds.

The importance of yesterday’s decision

cannot be over stated. Two of the judges on the US Supreme Court who have long

shown a great interest in copyright law and are both regarded as “liberals” on

the Court have seriously split with each other. The split is symbolic in many

respects of the overall state of affairs in copyright law, in which everyone professes

to believe in “balance”, as long it is their own definition of balance. The

result will be very inconvenient for the USTR in its trade negotiations in the

TPP, where the Americans will find it virtually impossible – though it has

rarely stopped them before – to say “Do as we say, not as we do”. No doubt, the

lobbyists will be hard at work in that forum in order to “policy shop” a

prohibition against parallel imports back into the US congress – but that won’t

be easy, to say the least.

Ironically, Justice Ginsburg was explicitly

very concerned about the future of US trade negotiations and treaties that are

still only a glint in the USTR’s and various lobbyists’ eyes – a concern which

many might find seriously out of place in a judgment of the US Supreme Court:

Quality King

left open the question whether

owners of U. S. copyrights could retain control over the importation of copies

manufactured and sold abroad—a point the Court obscures, see ante, at 33

(arguing that Quality King “significantly eroded” the national-exhaustion

principle that, in my view, §602(a)(1)embraces). The Court today answers that

question with a resounding “no,” and in doing so, it risks undermining the

United States’ credibility on the world stage. While the Government has urged

our trading partners to refrain from adopting international-exhaustion regimes

that could benefit consumers within their borders but would impact adversely on

intellectual-property producers in the United States, the Court embraces an

international-exhaustion rule that could benefit U. S. consumers but would

likely disadvantage foreign holders of U. S. copyrights. This dissonance

scarcely enhances the United States’ “role as a trusted partner in multilateral

endeavors.” Vimar Seguros y Reaseguros, S. A. v. M/V Sky Reefer,

515 U. S. 528, 539 (1995).

In any case, her reference to the Vimar decision is misplaced, since

the comment to which she apparently refers says that “courts should be

most cautious before interpreting its domestic legislation in such manner as to

violate International agreements”. In fact, not only are there no existing multilateral

international treaties or agreements that prohibit international exhaustion.

The TRIPS agreement expressly permits countries to come to their own conclusions

on this issue. The fact that the USA may now want to forbid international

exhaustion via future treaties should be of no relevance whatsoever to the US

Supreme Court.

An

aspect of this decision – which will be elevated no doubt to “sky is falling” proportions

– is the often heard suggestion that US publishers, entertainment companies, software

developers etc. may become reluctant to supply English language products to

developing countries at lower prices for fear of seeing them shipped back to

the USA as parallel imports. That argument may once have had some serious merit

– but is increasingly moot as so many of these types of products are now

provided digitally – and often controversially with DRMs of various stripes

attached, including regional coding. This opens up a whole new debate about

sale v. lease, and the future of TPMs, etc. Moreover, the emergence of mega e-commerce

entrepreneurs such as Amazon and the eBay phenomenon mean that the

sustainability of price discrimination models is in serious doubt anyway.

Finally, if students and other consumers in developing countries cannot get

their needs for English language products legally satisfied at reasonable

prices, they may resort to recourse to readily available online illegal sources

and their governments may turn a blind eye except for token efforts at

enforcement. That is simply a realistic observation. Don’t shoot the messenger.

The

debate about domestic and international exhaustion has been going on for over a

century. It is far from exhausted. But yesterday’s decision is a great victory

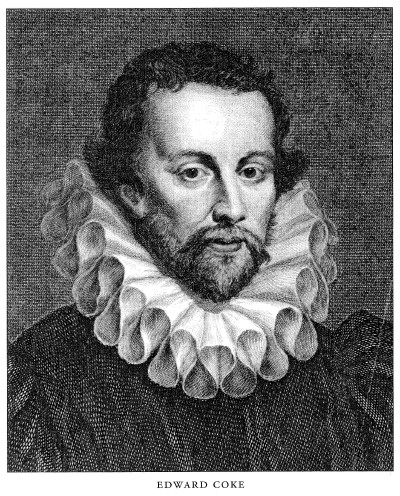

for free traders and those who believe in the majesty and the wisdom of the

common law (Lord Coke, no less who was referred to at length) and the role of

the judiciary.

In

closing, here’s the passage referring to Lord Coke (1552 to 1634) – which legal

scholars will no doubt find to be delightful:

The “first sale” doctrine is a common-law

doctrine with an impeccable historic pedigree. In the early 17th centuryLord Coke

explained the common law’s refusal to permitrestraints on the alienation of

chattels. Referring to Littleton, who wrote in the 15th century, Gray, Two

Contributions to Coke Studies, 72 U. Chi. L. Rev. 1127, 1135 (2005), Lord Coke

wrote:

“[If] a man be possessed of . . . a horse, or of any otherchattell

. . . and give or sell his whole interest . . .therein upon condition that the

Donee or Vendee shallnot alien[ate] the same, the [condition] is voi[d],

because his whole interest . . . is out of him, so as he hath no possibilit[y]

of a Reverter, and it is against Trade and Traffi[c], and bargaining and

contracting betwee[n] man and man: and it is within the reason ofour Author

that it should ouster him of all power given to him.” 1 E. Coke, Institutes of

the Laws of England §360, p. 223 (1628).

A law that permits a copyright holder to

control the resale or other disposition of a chattel once sold is similarly

“against Trade and Traffi[c], and bargaining and contracting.” Ibid.

With these last few words, Coke emphasizes

the importance of leaving buyers of goods free to compete with each other when

reselling or otherwise disposing of those goods. American law too has generally

thought that competition, including freedom to resell, can work to the

advantage of the consumer. See, e.g.,

Leegin Creative Leather Products, Inc.

v. PSKS, Inc., 551 U. S.

877, 886 (2007) (restraints with “manifestly anticompetitive effects” are per se illegal; others are subject to

the rule of reason (internal quotation marks omitted)); 1 P. Areeda &

H.Hovenkamp, Antitrust Law ¶100, p. 4 (3d ed. 2006) (“[T]he principal objective

of antitrust policy is to maximize consumer welfare by encouraging firms to

behave competitively”).

The “first sale” doctrine also frees courts

from the administrative burden of trying to enforce restrictions upon

difficult-to-trace, readily movable goods. And it avoids the selective

enforcement inherent in any such effort. Thus, it is not surprising that for at

least a century the “first sale”doctrine has played an important role in

American copyright law. See Bobbs-Merrill

Co. v. Straus, 210 U. S.

339 (1908); Copyright Act of 1909, §41, 35 Stat. 1084. See also Copyright Law

Revision, Further Discussions and Comments on Preliminary Draft for Revised U.

S. Copyright Law, 88th Cong., 2d Sess., pt. 4, p. 212 (Comm. Print 1964) (Irwin

Karp of Authors’ League of America expressing concern for “the very basic

concept of copyright law that, once you’ve sold a copy legally, you can’t

restrict itsresale”).

The common-law doctrine makes no geographical

distinctions; nor can we find any in Bobbs-Merrill

(where this Court first applied the “first sale” doctrine) or

in§109(a)’s predecessor provision, which Congress enacted a year later. See supra, at 12. Rather, as the

Solicitor General acknowledges, “a straightforward application of Bobbs-Merrill” would not preclude the

“first sale” defense from applying to authorized copies made overseas. Brief

for United States 27. And we can find no language, context, purpose, or history

that would rebut a “straightforward application” of that doctrine here.

Yes

– remembrances of the basic great principles of the common law do go better

with Lord Coke.

HPK

Rev.

March 20, 21 2013