Access Copyright (“AC”) and York University

have both filed applications for leave to appeal in the Supreme Court of Canada

(“SCC”) following the decision of the Federal

Court of Appeal (“FCA”) in York

University v. The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright), 2020

FCA 77 (CanLII), <http://canlii.ca/t/j6lsb>, (the

“FCA decision”) which I have discussed at length here.

I will

comment only in a very cursory way at this point. I and others will no doubt

have much to say in the future – either in the SCC on behalf of interveners or

in blogs, articles, etc. – or both. I have written frequently on my blog about

this case and related issues in the past and addressed the main issue in the

SCC in CBC v. SODRAC in the SCC – see below.

AC is,

of course, seeking to get leave to appeal the ruling that its Copyright Board

tariffs are not mandatory. It states, very astonishingly, in is Notice of Application

that:

3. This

case provides the Court with its first opportunity to consider

the tariff-setting

regimes under the

Copyright Act. The key question is whether tariffs approved by the

Copyright Board are enforceable against infringers who do not wish to pay them.

The Federal Court of Appeal held that they are not.

(highlight and emphasis added)

The

“first opportunity” comment, of course, is simply wrong – to put it very politely.

Justice Pelletier devoted the better part of 73 pages and 206 paragraphs in the FCA

decision totally vindicating the proposition that final – and obviously interim

– Copyright Board tariffs are not mandatory. His opinion cited and derives from

Prof. Ariel Katz’s landmark Spectre I paper that shows how the conclusion that tariffs are

not mandatory traces back to Vigneux v. Canadian Performing Right Society Ltd., 1943 CanLII 38 (SCC), [1943] SCR 348,

<http://canlii.ca/t/fslvq> and legislation tracing from 1936. Moreover,

the FCA decision explicitly relies not only on the 1943 SCC decision in Vigneux,

but to two other SCC decisions, namely Maple Leaf Broadcasting v. Composers,

Authors and Publishers Association of Canada Ltd., 1954 CanLII 62 (SCC),

[1954] SCR 624, <http://canlii.ca/t/22x4f> and, of course, of Canadian

Broadcasting Corp. v. SODRAC 2003 Inc., 2015 SCC 57 (CanLII), [2015] 3 SCR

615, <http://canlii.ca/t/gm8b0>. See

FCA decision, paras. 54, 72 and 73.

AC’s

memorandum does at least mention the Vigneux decision. However, it obviously and blithely ignores the

controlling SCC case of Canadian

Broadcasting Corp. v. SODRAC 2003 Inc., 2015 SCC 57 (CanLII), [2015] 3 SCR

615, <http://canlii.ca/t/gm8b0>, from less than five years ago in which the SCC

explained in a dozen paragraphs (paras. 101-113) why Copyright Board tariffs are not mandatory,

as argued in that case by me on behalf of Prof. Ariel Katz and Prof. David

Lametti, as he then was. Reference to that totally controlling SCC decision is,

incongruously, nowhere to be found in AC’s material. This decision was, of course,

relied on and followed in the FCA decision.

I cannot

resist recalling from an earlier blog of mine in 2012 the following passage about ignoring relevant and dispositive precedents in an appellate court:

In

any event, Prof. Katz mentioned the recent decision of Judge Richard Posner -

remarkably colourful even by this remarkable judge’s standards - concerning the

risk of ignoring relevant and dispositive precedents. Here’s the relevant

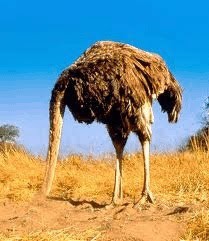

passage – with the illustrations included by Judge Posner himself:

When

there is apparently dispositive precedent, an appellant may urge

its overruling or distinguishing or reserve a challenge

to it for a petition for certiorari but may not

simply ignore it …

The

ostrich is a noble animal, but not a proper model for an appellate advocate.

(Not that ostriches really bury their heads in the sand when threatened; don’t

be fooled by the picture below.) The “ostrich-like tactic of pretending that

potentially dispositive authority against a litigant’s contention does not

exist is as unprofessional as it is pointless.” Mannheim Video, Inc. v. County

of Cook, 884 F.2d 1043, 1047 (7th Cir. 1989), quoting Hill v. Norfolk

& Western Ry., 814 F.2d 1192, 1198 (7th Cir. 1987).6 Nos. 11-1665, 08-2792

York University’s material deals with the fair dealing aspects of the FCA decision:

Issue 1: When determining whether copying in the educational

context constitutes “fair

dealing” under the Copyright Act, should the

analysis be conducted from the perspective

of the ultimate users (students), or from the perspective of

the educational institution they

attend?

Issue 2: When determining whether copying in the educational

context constitutes “fair

dealing” under

the Copyright Act, the analysis should

refrain from conflating factors.

Issue 3: For institutional fair dealing guidelines to be

“fair” for purposes of the Copyright Act, is there an

obligation for the institution to implement safeguards to ensure compliance

with the guidelines themselves?

Stay tuned.

HPK

(updated June 26, 2020)

(updated June 26, 2020)

No comments:

Post a Comment