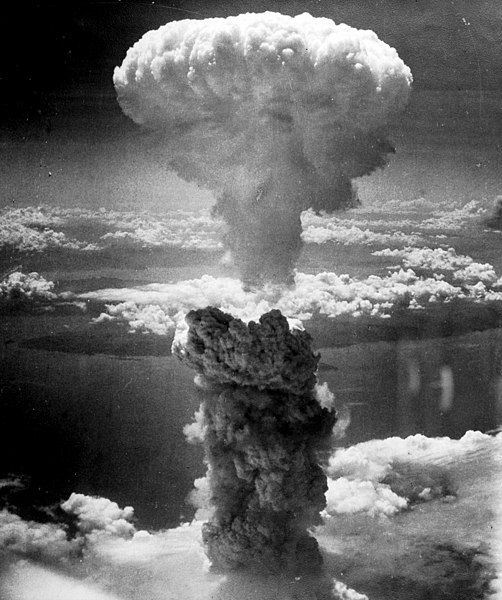

Charles Levy - Wikimedia Commons

There once was a time when proposed inaugural Copyright

Board tariffs were virtually bankable assets that would result in the financing

of very expensive hearings that almost invariably paid off quickly and many

times over – sometimes in the tens of millions or more.

Those essentially guaranteed good times and rich reward days for

collectives and their counsel now appear to be over.

Here is my second cut of comments on the Copyright Board’s landmark

decision regarding the Access Copyright (“AC”) proposed tariff for provinces

and territories, which I reported on shortly after it

was announced on May 22, 2015. No doubt, I and many others will have much more

to say another day. Michael Geist is already

off to very good start on his blog.

To recapitulate, the Board awarded a tariff of

11.56 ¢ per FTE (full time equivalent) for the period 2005-2009 and 49.71 ¢ per

FTE for 2010-2014. That’s less than 1% and about 2% respectively of what AC

asked for. According to the Board, the

tariff will generate a total of only about $370,000 over its ten year period –

which is likely only a small fraction of the costs involved in obtaining the

tariff.

This is probably the longest decision that the

Board has ever rendered. It took the Board more than 2.5 years from the hearing

to render this decision, which is a very long time – but that’s another matter.

To be fair, it is clearly complex. At 184 pages including the index, it is even

longer than the monumentally important inaugural retransmission

decision in 1990 that was the first and in some ways –

at least economically – the most important Board decision ever. The Board then awarded

a tariff worth more than $50 million a year 25 years ago – which was several

times more than anyone including the proponents ever expected. Even that

decision was shorter by six pages than the current decision – which results in

the one of the lowest dollar value tariffs that the Board has ever awarded. Interestingly,

the retransmission tariff decision was rendered less than five months from the

time that the 57 day hearing was concluded in May of 1990 - how times have

changed and not for better.

However, the current AC tariff decision may prove

to be one of the Board’s most important – precisely because it is so much less

than expected and precisely because it clearly is not worth even close to enough

to cover the costs of obtaining it. Since it was aimed at all of the provinces

and territories other than Quebec, ability to pay was definitely not an issue.

This decision is manifestly different than any other

Board decision that precedes it. The writing style is dramatically different.

The amount of detail and analytical rigour – both factually and legal detail –

is very different. There appears to be more of an “inquisitorial” involvement

that indicates that the Board will not simply rely on the adversarial process

and will ask its own questions and do its own thinking. Note the post-hearing

steps at the behest of the Board. Whatever the reasons,

the changes are welcome.

The Board has gone from almost a dearth of legal

reasoning and explicit factual underpinning and analysis to possibly the other

extreme – which is clearly a preferable excess if one has to choose between the

extremes. Whether such a detailed legal and factual analysis of the fair

dealing issues (about 50 pages in this case) was really necessary is debatable.

But it is definitely interesting and merits close analysis.

Overall, not only in hindsight but at the outset,

it seems and seemed fairly obvious that copying done by governments of third

party material will usually be for “research” purposes in the same way that

copying done by law firms is usually for “research” purposes. And this must, as

we all know now by heart, be given a “large and liberal interpretation”. Most

of this copying will be for a legitimate fair dealing purpose and meet the

further “factor” test. If the Board went overboard on this, it at least shows

that the Board has now finally taken to heart the important rulings of the

Supreme Court of Canada on fair dealing. Likewise, there’s a nine page discussion of what is “substantial” that

covers some important case law including that of the Supreme Court of Canada.

It is definitely good news that the Board appears

to have moved beyond comments such as referring to the Supreme Court’s CCH ruling

as “the unavoidable starting

point” on fair dealing and the Court’s reversal of the

Board’s fair dealing analysis in the K-12 Alberta case as “findings of fact”.

Another welcome development is the Board’s

recognition that Access Copyright’s repertoire is very limited, that the

Board’s previous contortions in the K-12 case to recognize a wider and

virtually unlimited repertoire were problematic, and that Access Copyright is

not entitled to be paid for the use of works that are not clearly in its

repertoire. The Board even commented negatively on AC’s repertoire “lookup”

tool, noting that it is not limited to actual repertoire but is based upon AC’s

conception of potential authorization.

The Board noted at para 119:

In short, Access considers in its repertoire

almost all published works, without regard as to whether there is any

relationship between the rights holder and Access.

And further:

[127] In the matter before us, payments have not

been made by Access in relation to the copying events captured in the Volume Study,

including to those with whom Access does not have an affiliate agreement. Since

no payments have been made, no agency relationship could have arisen between

the relevant owner of copyright and Access. The argument the Board accepted in

K-12 for including works of non-affiliated copyright owners in the

determination of the royalty rate is thus inapplicable in this matter.

….

[129] For the reasons that follow, we find that

this is not sufficient for us to include copying events where the owner of copyright

was not affiliated with Access as compensable for the purposes of determining a

royalty rate in this Tariff.

The Board certainly seems to be resiling from its

frankly untenable cheque-cashing implied agency theory in the K-12 case. See

para 136:

Access can only send cheques, and thus be able

to argue for the existence of an agency relationship, in relation to at most

0.005 per cent of copying from works of non-affiliated rights holders. Even if

we were to accept the premise that the sending of a cheque by Access in

relation to a copying event, and its subsequent cashing by the owner of

copyright in the work copied, forms an agency relationship in relation to that

particular copying event, it would remain that this would not happen for at

least 99.995 per cent of the actual potentially compensable copying of works of

non-affiliated rights holders that will occur during the Tariff period.

Clearly, Access Copyright and presumably other collectives must

now be able to prove what their actual repertoire consists of and cannot expect

to be compensated for repertoire for which there is no adequate chain of

entitlement.

What

will AC do now?

AC has is clearly “deeply concerned”. It says:

Access Copyright is deeply concerned with the Copyright Board of

Canada’s May 22, 2015 decision in the Access Copyright Provincial and

Territorial Governments Tariff, 2005-2009 and 2010-2014. The decision certifies

a nominal rate for the copying of published works by provincial and territorial

government employees and disregards the importance of licensing income to

creators and publishers in the digital economy.

We are currently reviewing the

decision and assessing all appeal options.

Access Copyright will almost certainly seek

judicial review (an “appeal” in laypersons’ terminology) of the current

decision. This will be the expectation and, in one sense, AC would have little

to lose. Judicial review is invariably much cheaper in terns if legal expenses than

the initial case itself – since normally there is relatively little additional

legal research that needs to be done and the record is what it is. It can’t be

added to.

On the other hand, AC must assess the very real possibility

of confirmation of the Board’s decision by the Federal Court of Appeal and/or

the Supreme Court of Canada, if it gets that far –which would be an even far

more serious loss indeed for it and which could affect other collectives in

many obvious and less obvious ways. At

first glance, such review could be an uphill battle in this instance – because

the Federal Court of Appeal and the Supreme Court of Canada are fairly

deferential to the Copyright Board overall – and very deferential on questions

of fact finding. In this case, we have 184

pages that are, arguably, mostly about fact finding and number crunching. Even

if the Board made some reviewable errors, which is far from obvious at first

reading, the result may be only be a very minor adjustment overall, given the

great care taken by the Board to determine what copies were compensable and why

or why not.

Moreover, any judicial review may attract some

interesting potential interventions – some of whom may be far from supportive

of AC, as AC is aware from the Province of Alberta case in the Supreme

Court of Canada where my intervener client, the

Centre for Innovation Law and Policy of the Faculty of Law University of

Toronto had a significant and perhaps determinative impact on the result.

Of course, there are other more positive options

for AC – which I have suggested before when I debated Roanie Levy

almost exactly a year ago at Brock University.

(Go to the ~24:30 minute mark). Maybe AC

should recognize that it is consistently losing in the Courts and in the court

of public opinion. Maybe it should drop its pending tariff cases at the

Copyright Board. Maybe it should drop its litigation against York University,

one of its best “customers”. And, of

course, it now has this defeat on its hands from the Copyright Board. And then

maybe it can sit down with its community and figure out how to provide a marketable

package of useful services based upon voluntary transactional licenses at

reasonable rates based upon its actual repertoire.

Access Copyright is not growing. It is struggling

to survive. It is spending an astonishing

29% of its revenues on operational expenses

– far more than the norm for established copyright collectives. It has an

infrastructure and resources that could still be put to good use. But its

survival will require much more and something much different than desperately aggressive

legal moves and a website makeover. I’m somehow sure that the AC Board of

Directors will be giving this much and urgent thought in the weeks, days, and maybe

even hours to come.

What

will be the Immediate Collateral Effects?

Here are some questions that are inevitably going

to be asked:

Province

of Ontario:

Why did

the Province of Ontario settle in 2011 for $7.50 per FTE (para 33) and agree to

a digital deletion provision (para 154)? The Board’s decision refused to

include a digital deletion provision and set a price that is only a small fraction

of what Ontario agreed to pay. In 2011, according to

Statistics Canada there were about 92,710 person employed by the “provincial

and territorial government” in the Province of Ontario. This does not include

teachers, health care workers, etc. The definition of an FTE employee caught by

the tariff apparently varies province by province (see decision, page 134) and

may or may not include health care workers, for example. It should not include educators,

who are covered by another tariff.

If we

take out the population of Quebec, which is not covered by the tariff, the

remaining population of Canada is about 26 million. Of this, Ontario counts for

more or less half at about 13 million. These figures

are rounded off from Statistics Canada. So, it’s probably safe to assume

that Ontario has about as many FTEs for AC purposes as the rest of Canada,

excluding Quebec.

There

about 120,000 FTEs in the rest of Canada, not including Quebec as counted by

the Board. (See page 152 of decision). Therefore, that’s probably a safe figure

to use for Ontario for FTE purposes, since Ontario’s population is about the

same as that of the rest of Canada, not counting Quebec.

And recall

that in the last Ontario election, Tim Hudak promised to fire 100,000 Ontario

public servants out the 1.1 million he counted. See this

article that points out some of the difficulties with determining these numbers.

So, to be conservative, let’s assume on the presumably low side that there are

100,000 FTEs in Ontario covered by the license. So, at an overpayment of $7 per

year for five years for 100,000 FTEs, we are talking about an unnecessary expenditure

of at least $3,500,000 – which is far more than the total liability for the

rest of Canada, excluding Quebec, for that period. And that’s probably a low

estimate of the Ontario FTEs covered by the agreement. That bad deal expired on

March 31, 2015.

True,

hindsight is always 20/20. But, even at the time of the Ontario settlement, it

was arguably predictable that this was far too generous a settlement in favour

of Access Copyright. Ontario had a previously negotiated rate of $3.12 per FTE

until 2010, which was determined in 2001 – three years before CCH (decision,

para 31). There is lots of evidence on the record as seen in this decision of previously

negotiated figures of even less than $3 per FTE in the past and that was BEFORE

the CCH case. These figures were known. Obviously, the CCH case presented a

strong reason to make the rate even lower after 2004. For some reason, Ontario

renewed in 2010 at the same pre-CCH rate of $3.12 per FTE.

Thus, it

looks like Ontario settled for an amount that is more than twice its own previously

negotiated already arguably too high rate in light of CCH.

So, why

would Ontario settle for more than twice the pre-CCH rate seven years AFTER the

CCH case? It would be no answer that Quebec was paying more. The Board examined

the Quebec situation in great detail and rejected the expensive COPIBEC license

entered into by Quebec as a proxy or benchmark for the rest of Canada.

If the agreement that expired on March 31, 2015

has not been renewed, it should be significantly renegotiated. If it has been

renewed at the $7.50 rate, at least foreseeably knowing that this decision was

long overdue and therefore could come at any time, other questions should

arise. In any event, a lot of questions generally might now be asked by Ontario

taxpayers about why this costly settlement was entered into and how the

Province deals with its copyright concerns.

The

AC Post-Secondary Tariff

What will the Board do now about the

Post-Secondary tariff, which is stuck between

a rock and a hard place perhaps now even somewhere in the twilight zone?

It is at once one of the most important files that Board has ever seen, and yet

the associations representing

universities and colleges (AUCC and ACCC respectively) have inexplicably withdrawn

from the hearing, withdrawn their objections

and left their members to the tender mercies of Access Copyright and the Board.

While it’s obvious that there is more copying in universities and colleges per

FTE than by employees of provincial governments, the Board can hardly ignore

the methodology and findings in the current case, which raises very similar

issues.

The

York University Litigation

What will this mean to the York University

litigation, which is based upon on the Post-secondary “interim tariff” that arguably should have been

challenged at the time by the AUCC and/or

ACCC but

wasn’t and now looks even worse in light of this decision? This litigation is

based upon the “mandatory tariff” theory and I have expressed

concerns about York’s response.

AC’s

“Premium” and “Choice” Packages

What will this mean to Access Copyright’s new “Access Premium” and

“Access Choice” offerings? [Why does this sound more like a cable TV

package? ;-)] Hard questions should be asked as to why universities should pay $18

per FTE for similar rights that Governments will now be paying less than $0.50

per FTE. That’s a 3,600% difference. While there is undoubtedly more copying

per capita in universities than in Governments, it is hardly likely to be

3,600% more. And what effect will these “voluntary” license rates have on the tariffs being sought at

the Copyright Board, which are much higher still – i.e. $35 for a university

FTE and $25 for other post-secondary FTEs for 2014-1017.

The

“Mandatory Tariff” Issue

Finally, what might be the impact on all of the

above of any ruling by the Supreme Court of Canada with respect to the

mandatory tariff issue, about which I made submissions on March 16,

2015 on behalf of Prof. Ariel Katz and the Centre For

Intellectual Property Policy as interveners? I won’t get into this now because

that case is currently pending before the Supreme Court. We may have decision

from the Court as early as September or October.

Other

Aspects

I and others have recently commented on the future

of the Board itself, which is a creature of statute and can be changed or

eliminated by statute, and is susceptible to regulations that can be readily implemented

by the Government pursuant to existing legislation. Personally, I believe and

have often stated that the problems with the Board’s procedure can be fixed by

regulations.

The Board is getting pressure from all sides to

speed up its procedures and to lower the costs of participation. It has formed

a working group to look at this. That has not gone too well, since certain

incumbent interests are resistant to change. There is also a recent study by

Prof. Jeremy de Beer commissioned by the Government, concerning which I’m

working on a fairly detailed commentary.

In the past, some have been worried that the Board

has become somewhat “captive” in the regulatory law sense to the collectives it

is supposed to regulate. However, some collectives may now believe that the

Board is leaning too far in favour of users. As I’ve pointed out, there are now

two decisions in the last year that will apparently result in two major

collectives failing to recoup their costs of obtaining a tariff – unless there

is some miracle arising from judicial review. The other is the Re:Sound Tariff 8 “Pandora” tariff.

Prior to last year, the one notable exception had been the ERCC.

It has apparently folded and never paid off its debts or distributed anything

to its royalty claimants. However, there were different considerations involved

in the ERCC (Educational Rights

Collective of Canada) story, and ERCC was at best a very niche collective.

Are these two decisions, especially the AC one

from May 22, 2015 a departure in significant ways from the past? Are they mere blips

on the long term chart? Has the Board now begun to take a different view of the

need for “balance” in the copyright collective realm? Has the Board taken on a

more “inquisitorial” role that will allow it to address the public interest

even in a fully contested case, and especially in important cases that may

proceed by default, such as the Access Copyright Post-Secondary Tariff?

These are important questions as summer

approaches. The next major event for Board watchers could be a puff of white

smoke announcing the appointment of a new Chairperson. But it’s probably unwise

to hold one’s breath, given that the post has now been vacant for over a year.

HPK